Do you feel richer as soon as you step off the plane in Kansas? When you visit family in the South, does everything in the grocery store seem cheaper? It’s not a figment of your imagination.

In many states, your $100 goes farther than others paying you back in essence. No surprise- it has a lot to do with taxes.

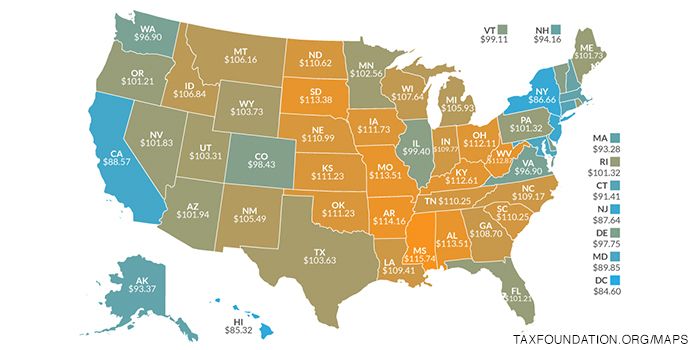

An interesting map from the Tax Foundation demonstrates the real value of $100 in each state by comparing average prices for similar goods. It demonstrates that in low-price states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Kansas having $100 delivers over $100 worth of value ($115.74, $113.51, and $111.23, respectively). In high-price states, such as the District of Columbia ($84.60), New York ($86.66), and California ($88.57), that same Benjamin Franklin leaves less in your wallet for the same expenses.

For those of us who live on the East Coast or West Coast but visit family or vacation in the Midwest, we notice the difference immediately. Many of us often dream of buying 3- and 4- bedroom homes with what we spend for a 1-bedroom apartment in a city like New York or Washington, D.C.

As the Tax Foundation explains:

Regional price differences are strikingly large, and have serious policy implications. The same amount of dollars are worth almost 40 percent more in Mississippi than in DC, and the differences become even larger if metro area prices are considered instead of statewide averages…

As it happens, states with high incomes tend to have high price levels. This is hardly surprising, as both high incomes and high prices can correlate with high levels of economic activity. However, this relationship isn’t strictly linear: for example, some states, like North Dakota, have high incomes without high prices. Adjusting for prices can substantially change our perceptions of which states are truly poor or rich.

…

The tax policy consequences of this data are significant. For example, because taxes must be calculated based on nominal income, the average New York resident pays significantly more in taxes than the average Kansas resident. But the Kansas resident actually has higher purchasing power, meaning that they get to pay lower taxes despite getting to have a richer amount of consumption.

Furthermore, this affects means-tested federal welfare programs. A poor person in a high cost area – like Brooklyn or Queens – may be artificially boosted out of the range of income where they are eligible for welfare programs, despite still being very poor. At the same time, many people in low-price states may be eligible for welfare programs despite actually being much richer than they appear.

The findings point to evidence that tax policy matters a great deal. Big government advocates often advocate for more money to provide much-needed services for the poor and middle class. If Americans knew just how much in purchasing power they were losing when taxes rose, I wonder if they would be more inclined to oppose tax-raising propositions.